“To whom it may concern”

A story about my grandfather

By Tjarco Schuurman

Opa

I don't think he ever realized it, but my grandfather influenced my life enormously. When we visited him when I was much younger, I always hoped he would talk about the war. He didn't talk about it much, only every now and then. When he did, he told how he escaped from a train heading to Germany and how he stole eggs from a farm. As far as I remember, he only told the good stories and I'm sure they were mostly the same ones.

My grandfather was born in Deventer in The Netherlands on August 1, 1918. His name is Albertus “Bert” Schoemaker, although I just called him by his official title and that was “opa” (gramps).

The story I want to tell you starts when my grandfather joined the Dutch army in October 1936, became corporal in May 1938 and Sergeant in March 1939 in the 1st Regiment Hussars.

1st Regiment Hussars in 1939

War

As we know now, the Netherlands was on the brink of war and when the Germans invaded the Netherlands in May 1940, his regiment was called up to fight the enemy between a defensive line called the Grebbeberg near Rhenen and Apeldoorn. His regiment also had to blow up bridges along the Apeldoorn Canal which is an interesting fact considering what happened 4 years later. During the German invasion my grandfather was lucky. Apparently, just before the war started, he broke his arm while directing traffic and he wasn’t able to fight on the frontlines. Although the Dutch soldiers were outnumbered and their rifles and guns were outdated, they fought bravely. When the Germans bombed Rotterdam, the Dutch government and army surrendered and my grandfather returned home. Thirty-nine men of his regiment didn’t. They died while fighting for their country.

Because he was no longer in the army, he joined the police and worked in various cities before he and my grandmother moved to the coastal town of IJmuiden in March 1941. This town is the gateway to the port of Amsterdam and during the war also home to the German Schnellboot (speed boats) and torpedo boats.

The train

As a police officer he could get close to places where not many others could. This allowed him to pass specific information to the local resistance group, who in turn informed England. That changed on December 11, 1944, when my grandfather and other police officers were ordered to come to the station in uniform. When they arrived, they were arrested. At first some men thought this was because they were trying to sabotage the Germans. And even though he never talked to me about it, I'm sure he had those thoughts too. He knew that working for and with the resistance was a risk, but he did it anyway.

If that had been the case, they probably would have been shot. Fortunately for the men, that was not the reason. The men were arrested because they were about to be sent to Germany for forced labor (arbeitseinsatz). Some men realized what was happening and fled before they arrived or escaped through windows of the room they were held. Ultimately sixteen police officers, including grandpa, were sent to various locations in the Netherlands before being put on a train to Germany on December 16, 1944.

And then the men made their own history...

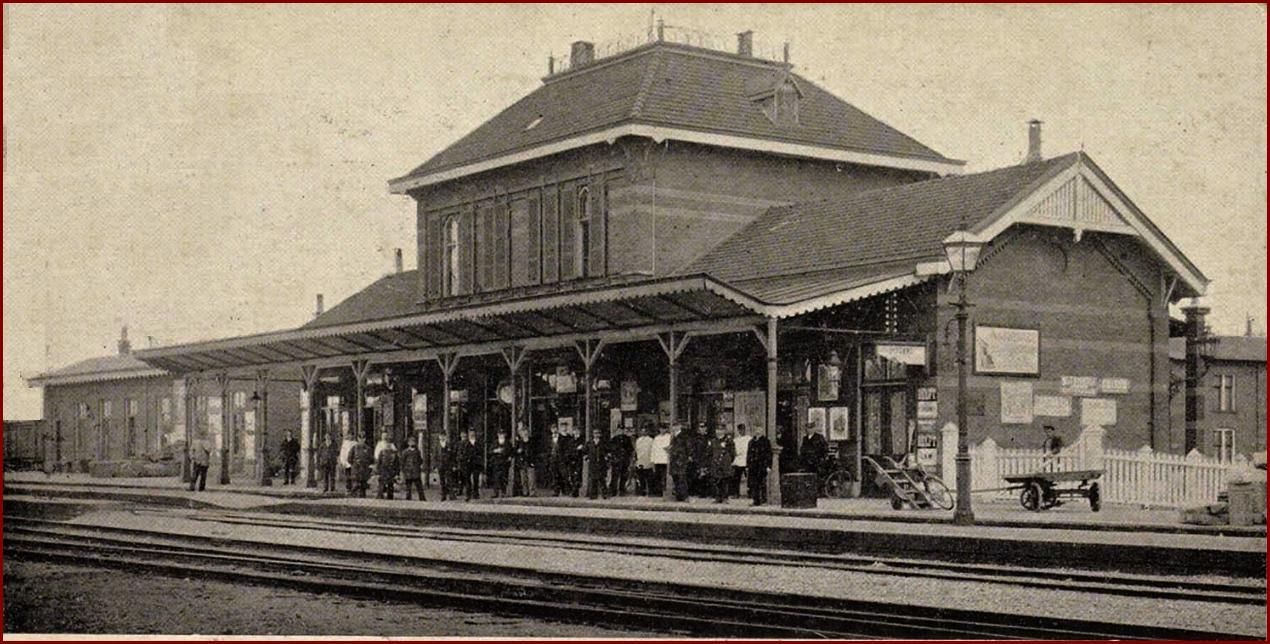

The men were sitting in different parts of the train. Still in the Netherlands, in Zwolle the German guards left the train and other German guards took over. It was there when one of the policemen opened a train compartment and a German asked him if he wanted to leave the train. Apparently, the new German guards were unaware that the police officers were arrested. Because they were in uniform and scattered all over the train, the Dutch police appeared to them as guards too. The Dutch quickly discussed a plan and their company leader went to the German officer asking him unto what train station they wanted the Dutch policemen on the train. The company leader said that by now there were enough guards on the train and they were not needed anymore. The German officer agreed and on Almelo station they disembarked the train in column and escaped under the eye of the enemy. From the train station they went to a befriended tailor in town and from there the men went into hiding.

Almelo treinstation before the war. This is more or less how it looked like in 1944. This beautiful building is gone now.

Becoming Canadian

It must have been a difficult time for my grandfather like it was for all citizens in occupied territory. It was winter, the coldest in a long time. Food was scarce and staying in hiding must have been a challenge. The allied forces were occupying the Southern part of the Netherlands and it took them until spring to move further North.

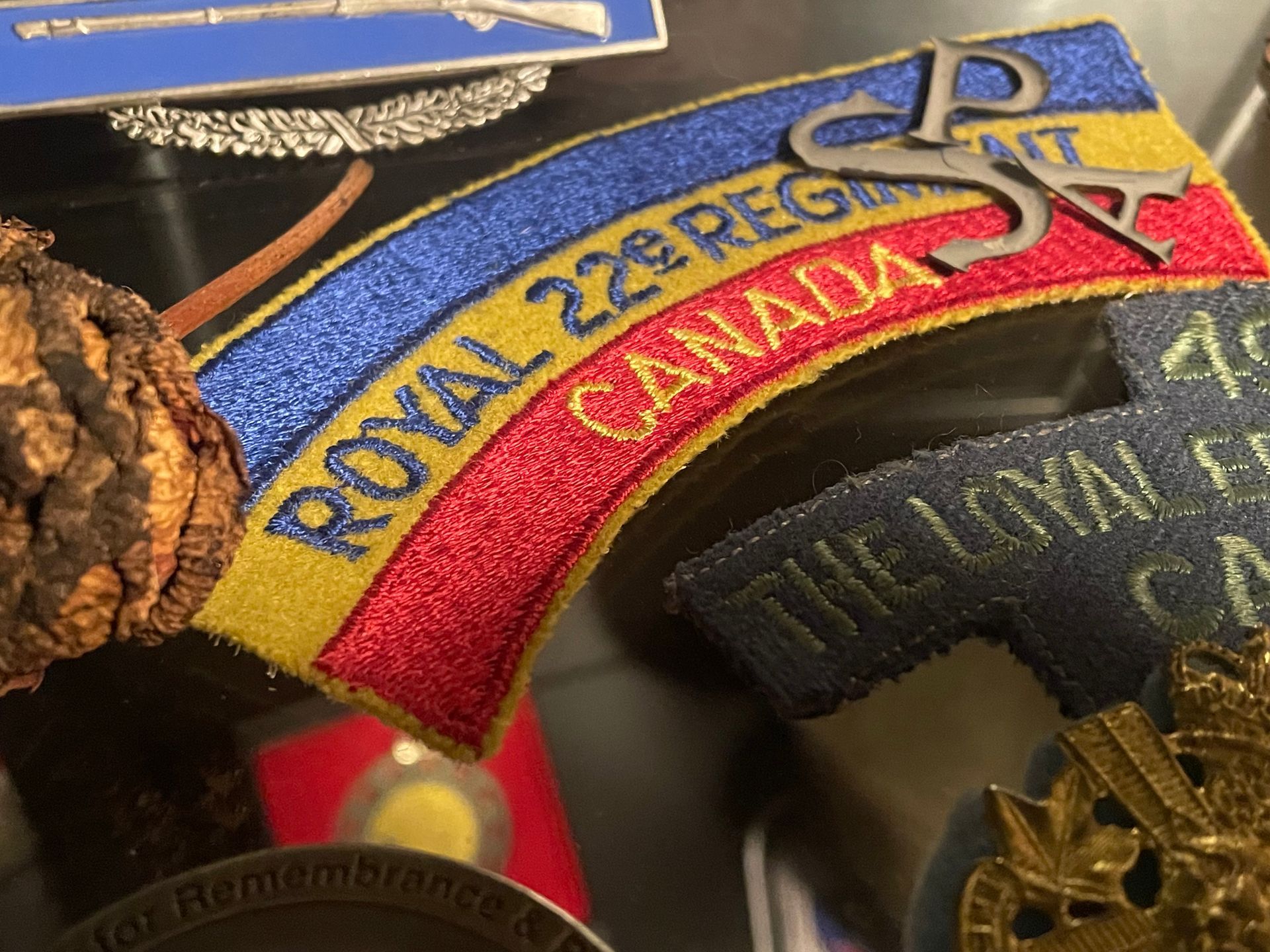

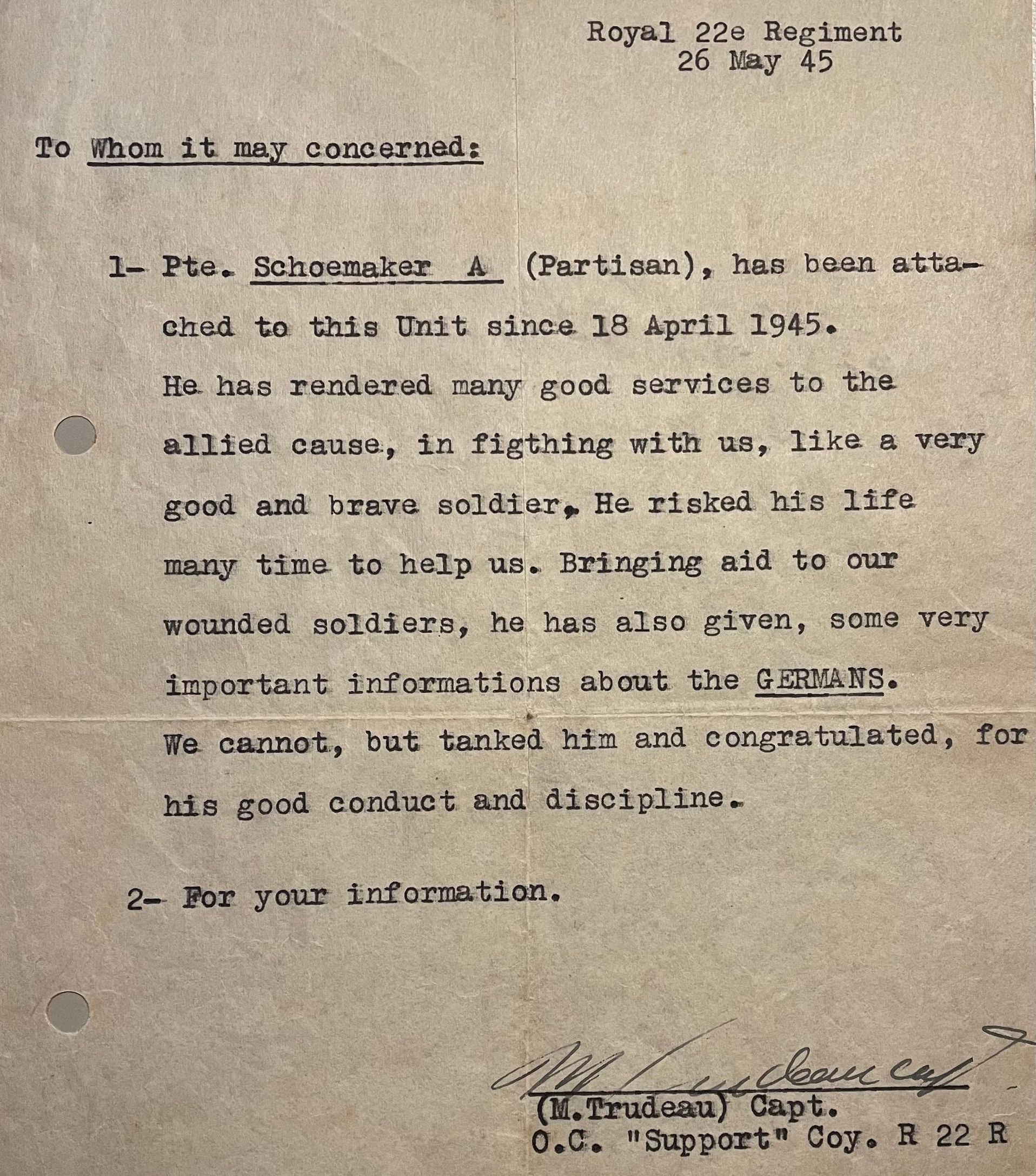

In April 1945, the liberation came closer. Canadian soldiers of the Royal 22nd Regiment (1st Canadian Division) were fighting their way from the East of the Netherlands to the West. Mid-April, they were coming through the area my grandfather was. The war diaries don’t mention him specifically, but they do mention Dutch civilians coming through the lines giving information about the enemy. According to a document an officer of the Canadians wrote, on April 15th, my grandfather joined the Canadian army as interpreter and general duty man. In fact, the letters show that he fought with them, risked his life many times and cared for the wounded. And as he shared earlier in IJmuiden, he again shared valuable information about the Germans.

At that point, the Canadians were just below Apeldoorn fighting the German army and finding a way to cross the Apeldoorn Canal. The same canal on which my grandfather’s unit blew up the bridges in 1940.

It’s typical my grandfather to manage to join the Canadian army. In our family, that part of who he was and how he managed to make things happen is something we always smile about. Especially because he joined this specific unit as an interpreter speaking Dutch, German and English. But the Royal 22 Regiment actually was a Canadian regiment from Quebec so French was the native language to most of the men. And gramps spoke no more than five words of French. The Royal 22nd Regiment, the “Van Doos”, (“English” for the French number Vingt-deux) was home to him for the remainder of the war.

To whom it may concern.

Being a soldier himself and given his character, I am sure he quickly became part of the regiment. The Canadians moved further west and soon the fighting ended and gave way to liberation. They liberated towns like Maassluis and Naaldwijk.

Naaldwijk is especially special to me because I worked at a flower auction there a few years ago. During my research on him I discovered that his regiment stayed in the auction buildings during the last days of the war. Unfortunately, the old buildings have disappeared and a kind of semi-modern building has taken their place. But I was standing on the same ground as him. And that made me proud.

It is also typical of my grandfather that he managed to get his superiors to write documents about his role in the police and in the Canadian army. The two Canadian letters I now possess begin with “to whom it may concern.” And that particular phrase is one I've thought about for a long time. Naturally he tried to have his work documented, which was smart just after the war. This way he could prove what he did.

The phrase “to whom it may concern” was probably not intended for us as his family, but the fact is that it does concern us. Maybe unintentionally. These documents make him a hero. It makes him the person I look up to and it makes him the person who planted the seeds in my brain for becoming a World War Two ‘historian’. He helped me shape my life into what and who I am today. And I am grateful for that.

After the war, Bert Schoemaker became a police officer again until his retirement.

In his footsteps

I miss him. I miss going to the Chinese restaurant with him. I miss the dry meatballs he used to make. I miss the fact that we were allowed 10 small candies per child, even though he knew we didn't count the candies in our mouths. I miss his calls asking me to come over and fix something he messed up on his computer, knowing that he actually wanted the company. But most of all, I miss not being able to tell him he is my hero. That I can't ask him anything anymore. And show him my gratitude for what he did. My grandfather died in 2001. Although he didn’t speak much about the war, doing research and walking is his footsteps feels like I am closer to him than before.

Sources:

Family documents

Book: De Velser Affaire from Guus Hartendorf

War Diaries Royal 22nd Regiment

Ministry of Defense (Netherlands)

Sytzama.nl

https://www.facebook.com/SchnellbootbunkerIJmuiden/

http://www.toenwasalmelonogmooi.nl/

https://archieven.coda-apeldoorn.nl/

Read about our journeys in our blogs

This is our Explore Diary